Will COVID-19 Increase the Jobs Divide?

By Maho Hatayama, Mariana Viollaz and Hernán Winkler / May-2020 /

The COVID-19 crisis and implementation of “social distancing” policies around the world have raised the question of how many jobs can be done at home.

But answering this question has proven to be an elusive quest, since researchers and policy makers cannot see in real time who is able to work from home during the pandemic.

For example, while working from home may not be optimal for several occupations in normal times, jobs’ tasks adjusted significantly during the pandemic. Consider the case of restaurants that quickly converted from sit-down service to take-out; or the number of family care physicians who conduct appointments via telemedicine; or Stephen Colbert, who has been doing his popular TV show from his well-appointed den.

And yet, there’s another key issue affecting mostly developing countries: Internet access is far from universal and this can reduce dramatically the number of jobs that can be done at home. Two examples help illustrate this issue. First, even if doctors in Africa could do basic check-ups on many of their patients online, that is not an option if they or their patients are off the grid. Second, while workers in call-centers would rank as very likely to work from home based on their intensive Internet use at work, it is not clear how many of them have a connection at home.

We attempt to get around these issues in a new paper.[1]

Estimating Jobs’ amenability to working from home

Most of the existing research on this topic relies on US-based measures of the type of tasks required by different occupations. However, occupations may differ in their task-intensity between the US and other countries due to differences in the organization of production or in the level of technology adoption. For instance, lawyers or business owners in developing countries may rely more on face-to-face interactions in person—rather than online—than their peers in rich nations.

In our study, we address this problem by constructing a new work from home (WFH) measure using skill surveys from 53 countries at different levels of economic development: 35 countries covered by the PIAAC survey, 15 countries covered by STEP survey, and 3 countries from the MNA region with information on tasks performed at work in their LMPS. Our WFH measure combines four components:

- A physical intensity and manual work component to capture tasks that are more likely to be location-specific and cannot be done at home, for example, because they require handling large items or use specific equipment;

- A face-to-face (F2F) intensity component, which captures tasks such as supervision or contact with the public;

- An ICT use at work component that reflects the fact that while some jobs may require substantial F2F interaction, some of such tasks can be carried out using ICT and do not necessarily have to be done in-person, and;

- A component considering internet connection at home to capture the likelihood of a remote setup. This is important since workers in developing countries who may use ICT at the workplace, do not necessarily have access to the same resources at home.

Looking at the individual components of the WFH measure, we find that the physical/manual intensity of jobs declines with GDP per capita, while F2F interaction increases. However, F2F intensive occupations also tend to be more intensive in ICT use, indicating that several of the tasks embedded in such occupations are more prone to be performed remotely. We also document the importance of distinguishing between ICT use at work and the availability of an internet connection at home. While both variables are highly correlated—i.e. countries where people use more ICT at work also have higher internet connectivity at home—there are some differences, particularly among less developed countries. For instance, the Philippines ranks relatively high in terms of ICT use at work, but it has relatively low levels of internet connectivity at home.

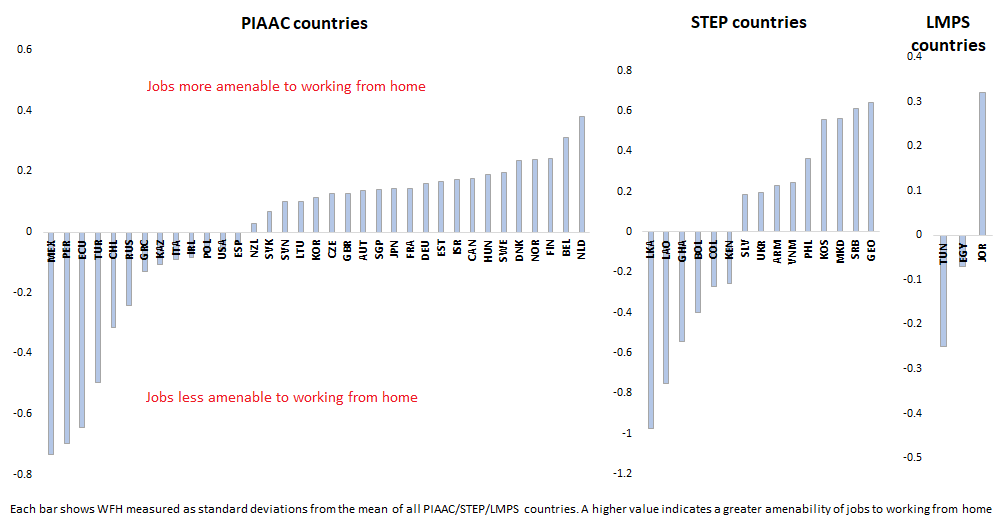

Combining the four components, we obtain a WFH measure with substantial cross-country variation (Figure below). The most vulnerable countries in the PIAAC sample are Turkey and those from the LAC region. In the STEP sample, countries from the ECA region have jobs more amenable to working from home, while the opposite is true for Sri Lanka, Lao, and Ghana. Among countries from the MNA region, Jordan ranks better than Egypt and Tunisia. In general, we find a strong association between the amenability of jobs to working from home, GDP per capita and internet penetration.

Our findings also show large disparities in terms of jobs’ amenability to working from home within countries. Jobs more amenable to WFH are more prevalent among workers with high levels of education, in salaried employment, and among younger workers. Workers with a formal job—either because they have a contract (PIAAC) or social security contributions (STEP and LMPS)—are more likely to have jobs amenable to WFH than informal workers. Women have a higher WFH measure than men. However, even when women’s jobs are more amenable to WFH, the unequal distribution of domestic work and childcare responsibilities within households may impact negatively on their chances to do it. Finally, sectors such as ICT, professional services, the public sector and finance, and occupations such as clerical work, professional and technician are more amenable to WFH.

Implications for policy

Our findings reveal that richer countries and more educated workers have jobs more amenable to WFH. As a result, social distancing measures may widen existing gaps between and within countries.

Our results also highlight the importance of policy efforts to reach informal workers as they are less likely to be able to WFH and to be covered by programs implemented through the social security or tax administration infrastructures. To a large extent, the between and within country divide in WFH amenability is driven by unequal access to ICT. These benefits of digital technologies should be considered by governments in developing countries when investing in broadband infrastructure.

___________________________

[1] Hatayama, M., Viollaz, M., y Winkler, H. (2020). Jobs’ Amenability to Working from Home: Evidence from Skills Surveys for 53 Countries. Documentos de Trabajo del CEDLAS Nº 263, Mayo, 2020, CEDLAS-FCE-Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

___________________________

It is allowed to reproduce this blog post, but it is requested to quote the source: Maho Hatayama, Mariana Viollaz and Hernán Winkler (May-2020). Will COVID-19 Increase the Jobs Divide?. Blog del CEDLAS, https://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/aumentara-el-covid-19-la-desigualdad-entre-trabajos